Saints, Cowboys, And Buffalo Soldiers

"General

Orders No. 1, issued in February 1881, abolished all military districts in the

Department of Texas. (Colonel Benjamin F)

Grierson took note of the service of the black soldiers from 1878-1880 of the

Tenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Fifth (Cavalry Regiments) from his

headquarters at Fort Concho in the District of the Pecos. They had constructed and maintained three

hundred miles of telegraph lines, guarded over one thousand miles of wagon

roads, and marched 135,710 miles. They

had conducted the successful campaign against Victorio and the Mimbres

Apaches. They had made the district so

safe that settlers flocked to western Texas."-- Debra J Scheffler, The Buffalo

Soldiers:Their Epic Story and Major Campaigns, 2015

Bartholomew J De Witt, whose beloved wife

Carolina Angela Garza died in 1866, paid $320 for 320 acres of land in the arid

quarter of Texas west of the 100th meridian and south of the 32nd

parallel around the time a nearby military installation received its third and

final name in 1868...

|

| Angela Garza De Witt and her patron saint, Angela de Merici, overlook the Concho River in John Noelke's 2005 sculpture, Las dos Angelas, located behind the visitor's center in downtown San Angelo |

Fort Concho (after brief incarnations as Camp

Hatch and Camp Kelly) sat near the junction of the Middle and North Concho

rivers at a site meant to overcome a lack of water for troops and horses-- the major deficiency of Fort Chadbourne which

had been established in 1852 in what later became Coke County to protect stage

coach routes and the few European descent settlers in the harsh and dry region...

|

| Wagon train settlers headed west pause for a respite at Fort Concho in this undated photograph from the late 19th Century |

The renamed military outpost would play a key

role in settling the American Southwest.

Its soldiers were charged with protecting settlers and keeping the route

to El Paso del Norte open at the same time they mapped the four hundred miles

of desert separating the Army garrisons of Fort Concho and Fort Bliss, working

in conjunction with men assigned to even more remote and isolated locations

such as Fort Stockton and Fort Davis...

Most of this grueling work fell to a group of

men called Buffalo Soldiers..

|

| Stylle Read included this realistic depiction of a Fort Concho soldier in the harsh and unforgiving West Texas desert in a 2012 mural devoted to the military heritage of San Angelo |

Where there are soldiers, there are goods not

readily available in military commisaries and Bart De Witt established a

trading post in an area referred to as “Over The River” to meet the needs of

troops and settlers alike. The collection

of shops and saloons that sprang up soon took the name San Angela, either in

honor of De Witt’s wife, her patron saint (Angela de Merici), or a relative of

the family who was a nun in San Antonio...

Santa Angela became the town of San Angelo,

thanks to a mishap with the Post Office which resulted in a bureaucratic sex

change for a town known for gamblers, prostitutes, and saloons. Among the rascals who added to the

misdeeds committed in the dusty desert settlement were the card sharps Carlotta

J Thompkins aka Lottie Deno aka Mystic Maude (and the prototype for Miss Kitty

on the Gunsmoke television series) and

John Henry “Doc” Holliday, a dentist best remembered today for a 30 second

gunfight at the O K Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. This outlaw past and reputation

as a dangerous frontier city eventually worked its way into popular American

music as “San Angelo”, a gunslinger ballad by Marty Robbins, who told a similar

story about an outlaw and his lover in El Paso...

|

| Born into Kentucky wealth, Lottie Deno chose the life of gambler in San Angelo and other western frontier towns. She is said to be the inspiration for Gunsmoke's Miss Kitty |

But, long before that, in 1866, following the

Civil War, Congress found itself impressed by the bravery of the 180,000 or so

black soldiers who’d seen service in the Union Army and decided to form cavalry

and infantry regiments composed of African-Americans. Several regiments were

consolidated after their creation and, by 1869, these men were assigned to one

of four regiments: the Ninth United States Cavalry, the Tenth United States

Cavalry, the Twenty-Fourth United States Infantry, and the Twenty-Fifth United

States Infantry. They were relatively

well paid for the times-- Buffalo Soldiers enlisted for five years with a

starting salary of $13 per month...

Despite the dangerous duties assigned these men,

their ability to lead themselves and plan complex military operations was

questioned. White officers commanded

them with few exceptions, the most notable of these being Henry O Flipper, who,

in 1873, became the first black man to receive a commission from West Point...

|

| Henry O Flipper, circa 1900. Despite his mistreatment by the military, Flipper went on to a long and successful career as an author, engineer, and political advisor |

[Flipper was eventually forced out of the Army

in what now appears to have been a racially motivated court martial involving

the disappearance of post funds entrusted to his care. Acquitted of charges of embezzlement, he was

nevertheless found guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman”

and dismissed from the service in June 1882.]

Sadly enough, a number of white officers,

including George Armstrong Custer of Little Bighorn infamy, refused to command black

soldiers. In Custer’s case, he believed

them inclined to cowardice and consequently considered it below his dignity to

ride alongside such men. His distaste

for black soldiers was so great that he turned down command of the Tenth

Cavalry, a Colonel’s position, and instead accepted a Lieutenant Colonel’s

duties with the Seventh Cavalry...

Among those who disagreed with Custer’s

assessment of African-American courage and fighting skills were Native American

tribes of the Desert Southwest and the Great Plains who first referred to the

black infantry and cavalry troops as Buffalo Soldiers. It was a term bestowed with respect. Disagreement exists as to whether the

Cheyenne or the Comanche first used the term.

Several theories have also been advanced to explain the origin of the

Buffalo Soldier nickname: the curly black hair of the soldiers, their ferocity

and bravery in battle, the buffalo hide coats they wore in the winter...

|

| 10th Cavalry soldiers on the parade grounds of Fort Davis |

Regardless of how they got their name, black Buffalo

Soldiers made the Great Plains safe for white settlers at the expense of the

red man in quick order, building roads and telegraph lines and escorting mail

between skirmishes with the native settlers.

The focus of their duties then shifted southwest to the dry country of

West Texas. In April 1875, regimental

headquarters for the Tenth Cavalry were transferred to Fort Concho (which

simultaneously also became home base for the Ninth Cavalry) where its soldiers continued the work they’d

begun on the Kansas plains at Fort Leavenworth...

Soldiers assigned to Fort Concho were primarily

responsible for patrolling the previously mentioned southwestern quarter of

Texas, a land of desert grasslands dotted with xeric shrubs as well as large

stretches of barren country almost entirely lacking in vegetation. Readers who are familiar with the western

half of Texas would appreciate the difficulty of their duties even if the hard

country of the Concho Valley and Trans-Pecos had been the only area of

responsibility for these men. But they

also found themselves traveling northward to the equally harsh regions of the

Llano Estacado and Panhandle to fight Comanches or map the sparsely populated

landscapes...

One of the greatest miltary challenges the

Tenth Cavalry faced came in 1880 when it became part of the campaign against

the Apache chieftain Victorio and his band.

Led by Colonel Benjamin Grierson, who had commanded the regiment since

its founding in 1866, the Buffalo Soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry marched ten

thousand miles of desolate country to successfully engage Victorio’s men at

Tinaja de las Palmas and Rattlesnake Springs...

|

| Benjamin Grierson commanded the 10th Cavalry from its beginnings in 1866 until his retirement from the Army in 1890, refusing numerous offers of transfer to less grueling assignments |

[Eventually killed in battle in Mexico, Victorio

was, like Cochise, a son-in-law to Mangas Colorado whose torture and murder by

American soldiers in January 1863 while under a flag of truce inflamed the

Apache. Victorio’s sister Lozen was also highly regarded for her courage in battle,

her skill as a horsewoman, and what seems to have been a kind of prophetic

ability and clairvoyance allowing her to see things at a distance and forecast

the outcome of events. After her

brother’s death, Lozen allied herself with Geronimo and continued to battle for

her people until her own death from tuberculosis in 1890.]

Grierson also wore the hat of commander of the

Military District of the Pecos from 1878 to 1881. When he relinquished those duties, he noted

“a settled feeling of security, heretofore unknown, prevails throughout Western

Texas.” A year later, in 1882, the

regimental headquarters of the Tenth Cavalry was transferred deeper into the

desert to Fort Davis in Texas across the Pecos to contend with the remaining

threats posed to settlement...

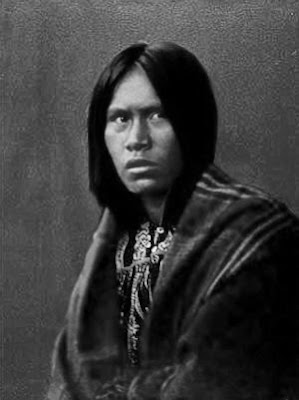

|

| Lozen, sister of Victorio and a fierce warrior in her own right, was said to possess supernatural powers of prophecy and clairvoyance |

The tenor of the times was such that Grierson, originally

a music teacher who lacked West Point credentials but who’d overcome a personal

fear of horses to prove his mettle during the Civil War, was viewed by his

peers with a certain disdain not only for his unwavering support of the black

soldiers he commanded (from 1866 until 1890) but also for his strong respect

for the Native Peoples he fought...

While the role of the Buffalo Soldier in settling the frontier is slowly

becoming more widely known, the fact that about one in four post Civil War

Texas cowboys was a black man (with Mexican cattle hands being at least as

numerous) still eludes most of us.

British born film documentary producer John Ferguson suspects the lack

of cowboys of color during in the movies and television shows from the heyday

of Hollywood westerns lies at the root of our general ignorance about the role

minorities played in taming the frontier...

|

| Mario Van Peebles in Posse |

One notable example of the lack of color in

Hollywood is John Ford’s The Searchers,

a 1956 film starring John Wayne as a Civil War veteran whose niece has been

abducted by Indian. The Alan Le May

novel on which Ford based his film was inspired largely by the story of Brit

Johnson, a black cowboy whose wife and children were taken prisoner by the

Comanche in 1865...

Despite this under-representation of the black

role in settling the American West, the movie industry didn’t totally ignore

the subject. A sampling of these films:

in the 1920s, Bill Pickett, an African-American cowboy credited with inventing

the “bull-dogging” rodeo event starred in a film produced by the Norman Film

Manufacturing of Jacksonville, Florida.

Herbert Jeffrey, who later toured with Duke Ellington, played the lead

in 1939’s Harlem Rides The Range. In

1972, Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte teamed up for Buck and The Preacher as a wagon-master and con man leading freed

slaves west. A quest for vengeance

drives 1993’s Posse with Mario Van

Peebles...

Black cowboys, especially those born into

slavery, often found a better life on the range than they could have elsewhere

in a state that had allied itself with the Confederacy. The reason for this was fairly simple. Survival of men working together in the hard

land of the American West depended on trust.

A man had to rely, like a soldier in combat, on the man next to

him. Too much prejudice could easily

prove fatal. As cattle driver Charles

Goodnight said of his friend Bose Ikard, born into slavery in Noxubee County,

Mississippi, “(I) trusted him farther than any living man. He was my detective, banker, and everything

else in Colorado, New Mexico, and the wild country I was in”...

Historian Mike Searles has noted the range

offered another form of equality for former slaves-- there were few bosses to

tell him what to do. A black cowboy

often had the unenviable task of being the one to break unridden horses. But you might also find him as the camp cook

or the man whose job it was to sing softly and keep restless herds calm when

there was a hint of a desert thunderstorm on the horizon...

THE

MARKETPLACE

http://louis-nugent.artistwebsites.com/

Follow and Like Louis R Nugent Photography on Facebook @ louisnugent22.

CREDITS

Note: All

photographs and research for this essay were located through Google Images or

Wikipedia and other readily available public materials, without authoritative

source or ownership information except as noted: photographs of Las dos Angelas, Christmas at Old Fort Concho, and Stylle Read mural by Louis R Nugent; Still of Mario Van Peebles in Posse (1993) from http://ia.media-imdb.com/; Lottie Deno from http://www.legendsofamerica.com/; 10th

Cavalry at Fort Davis from http://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/programs/buffalo-soldiers/;

wagon train at Fort Concho from http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/forts/images/travellors.html;

origin of Buffalo Soldier nickname and racial prejudice against black soldiers

from http://www.buffalosoldiers-amwest.org/history.htm; Custer comments from http://www.deseretnews.com/article/496071/BUFFALO-SOLDIERS-GOT-THE-LAST-LAUGH-ON-CUSTER.html?pg=all;

chronology of Fort Concho: http://www.fortconcho.com/forms/A%20Fort%20Concho%20Chronology.pdf;

http://www.vq.com/buffalo-soldiers/; http://texasalmanac.com/topics/history/frontier-forts-texas;

Grierson’s comments upon relinquishing his command from Fort Concho: A

History and a Guide, James T Matthews,

Texas State Historical Association Press, 2013; black cowboys from http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/15/world/black-cowboys/;

Black Cowboys, Teresa Paloma Acosta,

Handbook of Texas Online; Mike Searles observations from http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21768669;

black western films from http://www.separatecinema.com/exhibits_harlem.html